Discovery is a foundational principle of service design. It’s a process that emphasizes designing services with the user at the centre.

Core principles of service design include:

- Conducting user research to build empathy and understand the needs of users

- Building prototypes to serve as early models of a service

- Testing services regularly with real users to see if the service is working as intended

By understanding the people who will use a service, we can create solutions that truly work for them. Service design prioritizes engaging users throughout the design process, ensuring decisions are grounded in observation and evidence—not assumptions.

This guide provides recommendations and helpful tips to set up your research project.

It covers both qualitative and quantitative research methods, enabling you to gather the insights needed to make informed design decisions. Use this guide flexibly, aligning your research approach with the level of detail required to confidently move forward with building and testing prototypes.

What discovery is not

Discovery is not about finding solutions — it’s about understanding problems.

Avoid premature assumptions: Don’t jump to solutions before completing your research. Discovery focuses on uncovering root needs and challenges.

It’s not confined to a fixed scope: User research is dynamic and may lead to insights that challenge initial expectations.

Discovery may disprove assumptions: If a presumed problem is not validated, that is a success. It offers clarity and direction.

What discovery is

The goal of discovery is to define user problems and objectives, not to gather evidence for a predetermined solution. This stage is about deeply understanding users and the challenges they face.

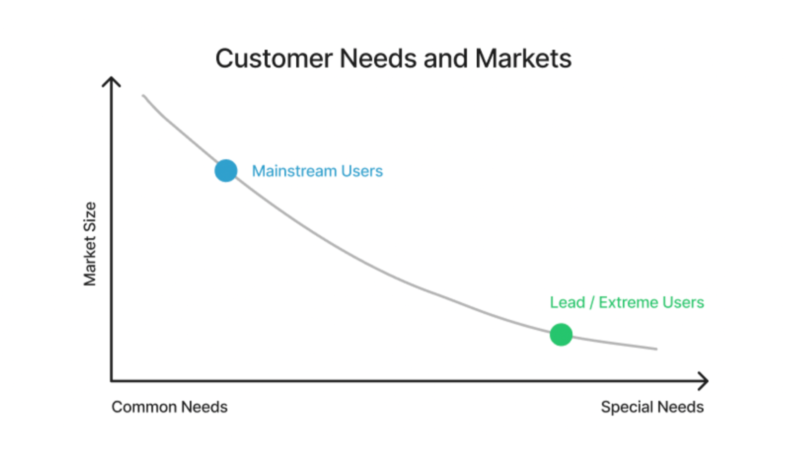

Extreme users

Extreme users interact with products in unconventional ways or have unique needs. Observing their behaviour can highlight friction points and opportunities that might otherwise go unnoticed.

Key characteristics

- Use products in ways that differ significantly from the average user

- Often have needs that fall outside typical use cases

Why they matter

- Solving their problems can improve the experience for a wider audience

- Their unique usage patterns can inspire innovation and reveal latent issues

Lead users

Lead users are ahead of emerging trends and rely heavily on products in their daily work or personal routines.

Key characteristics

- Experience needs ahead of mainstream customers

- Use products regularly and depend on them for their operations or success

Why they matter

- They directly benefit from product improvements, making them highly motivated to provide actionable feedback

- Lead users often innovate on their own, offering ideas that can shape new features or products

- Engaging with lead users can help you identify emerging customer needs sooner, allowing you to stay ahead of market demands

- Their insights can inform strategies that ensure your product remains relevant as trends evolve

Creating a research plan

Formulating a research plan can feel overwhelming, with the volume of potential qualitative and quantitative sources. While there may not be a single “right” way to conduct research, there are best practices that can help guide the process.

Remember: the goal of discovery is to define user problems and objectives, not to validate a solution.

Get context before conducting interviews

Customer feedback: Chances are the business you’re researching already has a log of customer requests, possibly in a tool like Productboard. Begin here and identify themes.

Stakeholder interviews: Speak to the departments that talk to customers daily. Share your theme analysis to validate or deepen insights.

Analytics: Your company may have access to tools like Mixpanel or Heap, allowing you to analyze actual user behaviour. Align this behavioural data with the themes you identified — new questions often emerge here.

Literature reviews: Literature reviews help you understand the current knowledge in your field, including boundaries, limitations and underlying theories. This context strengthens your research direction.

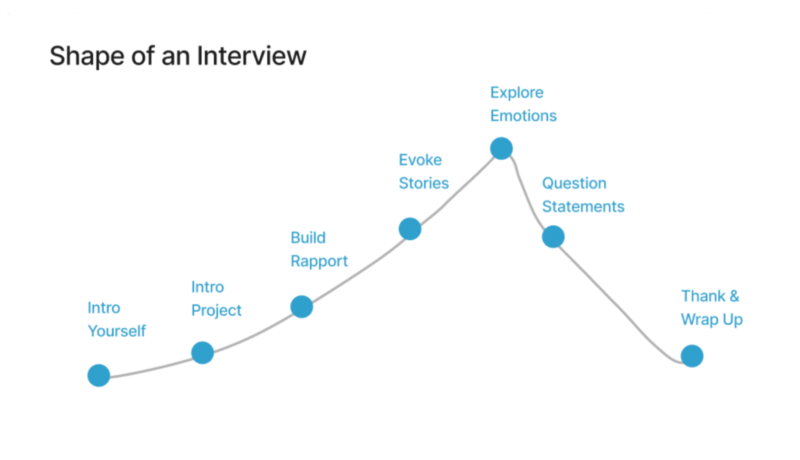

Plan your interviews

Identify your research goals: Be specific about what you aim to learn. For example: “Understand why users choose to create an account vs not so we can convert more users from guests to accounts.”

Identify and order themes: Organize questions into natural topics to create a smooth conversational flow.

Brainstorm questions: Record every possible question without filtering.

Refine your questions: Remove redundancies, clarify vague prompts and ensure alignment with your goals.

Identify your target audience: Define key roles, demographics or lead/extreme users relevant to your research.

Write a good screener: If you’re using a recruitment tool, include thoughtful criteria to ensure you speak to the right participants.

Pro tip: Asking questions in the same order during every interview will make synthesizing insights significantly easier.

Conducting interviews

Ask open-ended questions: Avoid yes/no prompts and avoid framing choices for participants.

Ask for specific past examples: Prompts such as:

- “Can you tell me about the last time that happened?”

- “Can you walk me through a specific example?”

Avoid generalizations: Bring participants back to concrete moments when they say things like “typically” or “usually.”

Continue to ask why: Clarify meaning rather than assume intent. Don’t assume you understand what participants mean. Ask:

- “Why is that hard?”

- “Why did you do that?”

- “Why do you say it feels like a game?”

Let the participant lead: Unexpected directions often reveal deeper context.

Allow for silence: Give participants time to think before responding.

Avoid asking “Do you like it?”: Instead focus on behaviour and value:

- “How does this feature fit into your workflow?”

- “What’s missing that would make this easier?”

Final thoughts

You’ll typically start seeing patterns after 6 to 12 interviews. If you’ve conducted more than that and insights still feel scattered, take a step back. It might be a sign that your themes are too broad, your participants aren’t well-matched to your goals or your questions need refining. That’s not a failure—it’s part of the learning process.

Great research takes practice. With each project, you’ll sharpen your ability to ask better questions, listen more deeply and uncover the insights that lead to truly user-centred design.

Tag

Related Articles

Samiksha Makhijani RGD, Deanna Loft RGD, Reesa Del Duca RGD, Allison Charles, Crispin Bailey RGD