What does your design profession look like vs your design practice?

Written by Anda Lupascu RGD

In the world of design, there’s often a quiet tension between what we do for ourselves and what we do for others. Most designers today, knowingly or unknowingly, fall into one of two categories—or perhaps embody both in varying degrees.

In this article, Anda Lupascu RGD shares her experience of the distinctions between design as a practice and design as a profession and how these two aspects shape the work and identity of designers. In Anda's view the distinction lies in the type of energy we bring to our design work. A professional is an individual who talks the talk, has a business plan, adds value through design and executes briefs to perfection.

Design practitioners are obsessive about their work, work every day, whether on a brief or not, question themselves, their work and even design as a whole throughout the process and are possibly selective about the type of work they do. Having a design practice is like having a yoga practice. Some days, it’s more flowy than others, and sometimes it hurts, but the important part is just showing up. It’s the work you do for yourself. This is the soul of design work. It’s a little bit like being an artist.

“A design practice is where freedom thrives and a profession is where success thrives. A design profession without a design practice can become soul-less. A design practice without a design profession can get groundless.”

Anda Lupascu RGD

We asked Anda about her experience, and she shared a key lesson from her master's degree in design that has stayed with her more than anything else.

During my studies, I felt a lot of tension when trying to learn new tools and skills that I thought would help me become a better designer. This meant skills that would get me a job after graduating, such as coding and video editing. However, the expectations of my professors were, first and foremost, to present artfully researched ideas and topically relevant concepts. I was afraid that their expectations were too abstract, and that they were not interested in the practicality of the work they were pushing me to do. I felt stuck and unable to figure out what they wanted.

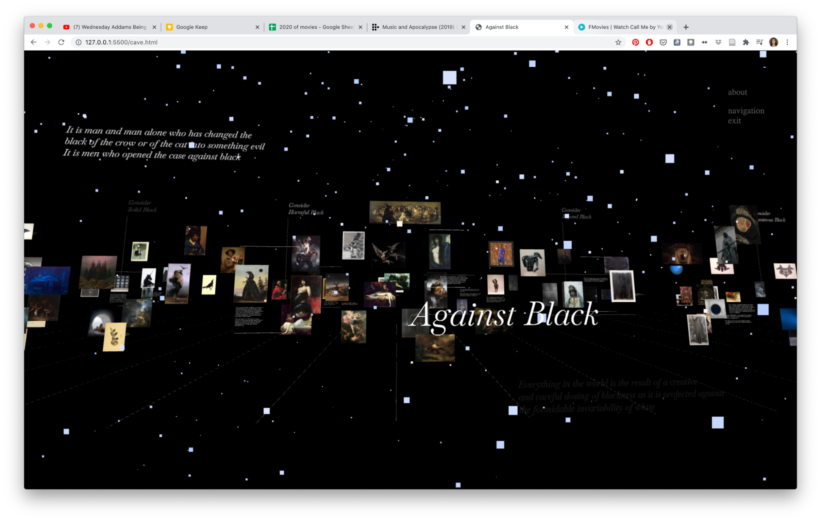

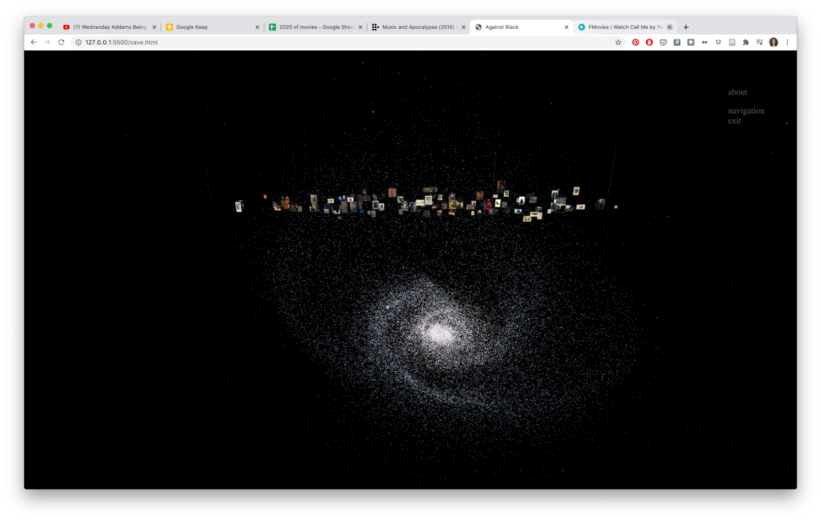

For example, I worked on a project which was perhaps not the strongest conceptually, however I had challenged myself to learn how to code using a VR library, and I was quite happy with the outcome of my efforts. I created a virtual-reality gallery of images, floating in a dark space, which could be visited using a VR headset or through a browser. Granted, a floating gallery was not the most impressive outcome, however for me, a newbie in this space, I was very proud of my efforts. I nearly failed this project and got a lot of neutral to negative feedback. I then realized that our expectations for “experimentation” were different.

Anda's project "Against black” a VR gallery exploring the colour black: voids, darkness and non-being.

I was hearing the phrase “design practice” a lot: “What is your design practice?” “How does this work inform your design practice?” And for me, these questions were all new. Doesn’t “design practice” mean I am practising design? Simple as that? If I am learning to code, I am "practising my design skills" in a new space, learning new things and even if the outcome is rudimentary, it is, by definition, practice. I learned that this was not the case.

After being pelted with the question “What is your Design Practice?” over and over for two years, I finally figured out what I was really being asked. I framed it for myself as Practice vs Profession. The awareness of the difference provided me with clarity. Wanting to learn new skills can be a part of my Practice as long as I investigate something I believe in. Learning new skills for new skills’ sake falls under the profession category, and I am doing it for professional reasons. My professors would not let that fall under Design Practice because I was not pushing myself as a designer but fulfilling market expectations. And as much as it frustrates me to admit it, they were right in that respect.

I remember one of my classmates was fascinated with printing posters by hand and woodblock printing. He built his own printing press over the course of a year, going through multiple iterations (some hilarious) and learning how to do metalwork. He was learning new skills within the context of his design practice, including his personal fascination with analog printing. The lecturers were very happy with him. (https://nickmonromeares.com/Thesis-Project). On the other hand, I was trying to learn skills first without properly framing why – I wasn’t clear on my Practice. I also realized that having a practice is a very personal, vulnerable and honest process. You have to be able to admit what you’re really interested in and pursue it at all costs. I realized I hadn’t been brave enough to do that.

However, that's not a bad thing. Now that I know what I’m looking for and what I am missing, I feel much more at ease about pursuing it. Realistically, I don’t know how much space I have for developing a practice when I have to pay bills, but the tension is certainly lessened. The experience of getting a Master's in design was only the first step in developing my Design Practice, while I continue in parallel with my rather more successful Design Profession.

The example I gave above of my classmate’s printing press is a great example of a project fulfilling a Design Practice with the potential to fulfill professional demands. In creating a printing press, he gave himself a unique selling point for any client looking for uniqueness and personalization in their brand designs.

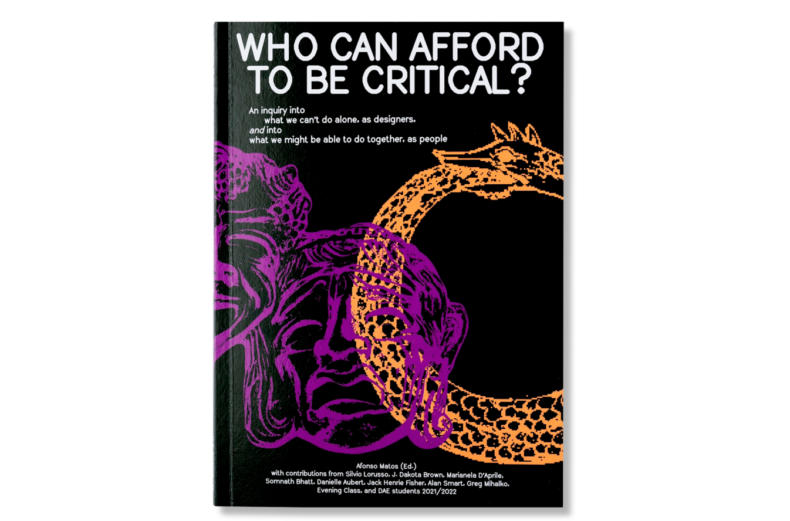

Who can afford to be critical?

Another example is a classmate who published his thesis book after graduation, a book which has been very popular in the design space, asking important questions about design. In this case, his Design Practice was a critical inquiry into the heart of design, fulfilling professional demands by being an intelligent and well-informed voice in the space and publishing a book.

For both examples above, there is potential to become financially viable, but this viability was not the intention, nor guaranteed.

Personally, I do not yet have examples of blending my practice with professional demands; it is a work in progress. My own thesis project was an abstract short film exploring the place of trees in a climate-conscious world. It's a tough sell, to be sure.

This is the golden question: how do we convince those who have funds to trust your vision, and how do we maintain our integrity in doing so? For my classmates, the quality and honesty of their work got their attention first and perhaps sponsorship second. It is much more difficult to gain this type of trust or interest in a corporate environment, so most of the work comes from designers. Design Practices usually live within the arts space - design weeks, exhibitions, etc.

Personally, I am interested in energy exchanges, working within my community and building a network of common interests and values that can lead to a natural interest in the outcomes of the experimental work of a design practice. I am focusing on building up trust close to home and working for Practice first and money second.

Tag

Related Articles